Pregnancy shrinks parts of the brain, leaving 'permanent etchings' postpartum

A study tracks how the structure of the brain changes during pregnancy, drawing on brain scans gathered before, during and just after one person's pregnancy.

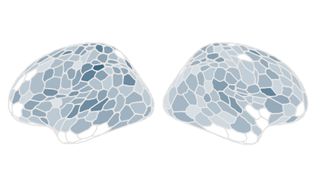

Pregnancy may cause more than 80% of the brain's gray matter to shrink, leaving "permanent etchings."

That's what researchers found when a pregnant neuroscientist underwent more than two dozen brain scans throughout her pregnancy and for two years postpartum. After pregnancy, the new mom regained some gray matter, which includes both the cell bodies of neurons and the connections between them. But much seemed to be gone for good.

On average, there was a 4% decrease in gray-matter volume within the affected brain areas, said Emily Jacobs, an associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) and co-senior author of the study.

"That's similar to the amount of reduction in puberty," Jacobs noted at a news conference Thursday (Sept. 12). Hormone surges in puberty come with a dip in gray-matter volume, as the brain prunes excess tissue so it can run more efficiently. Something similar may happen in pregnancy, Jacobs suggested.

Related: Menstrual cycle linked to structural changes across whole brain

"Sometimes people bristle when they hear that gray-matter volume decreases during pregnancy — like, 'That can't be a good thing,'" she said. However, "this change probably reflects the fine-tuning of neural circuits, not unlike the cortical thinning that happens during puberty."

That fine-tuning may forever change the brain. "Many of these changes seem to be what you might think of as permanent etchings in the brain," Jacobs said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, other changes seen in the study were temporary. During the first and second trimesters, white matter, the insulated wiring between neurons, grew more robust.

"We think of it as like a tube or like a straw," Liz Chrastil, an associate professor of neurobiology and behavior at University of California, Irvine and senior co-author of the study, said at the news conference. When white matter is robust, water flows straight through it without pooling or diverting it and similarly relays information more efficiently.

But the scans showed that white matter returned to baseline by birth.

"I'll sort of spill the beans — which is that I'm the person who is the participant who did this," Chrastil revealed at the news conference. "This project was actually quite an intense undertaking." The team didn't begin analyzing the scans until all of them had been collected, so neither Chrastil nor her colleagues knew how her brain was changing until afterward.

Chrastil said she didn't experience "mommy brain" or pregnancy complications, such as the blood-pressure disorder preeclampsia. Thus, her data could be a "very nice baseline" to compare with complicated pregnancies that might affect the brain differently, she noted.

Preeclampsia, for example, affects the brain's blood vessels and boosts the risk of stroke and vascular dementia. Other conditions, such as migraines and multiple sclerosis, often improve during pregnancy, and it's unclear why. Detailed brain maps like Chrastil's could shed light on how the brain typically changes in pregnancy and what might differ in the context of disease, Chrastil and Jacobs said.

While this study looked at only one person, the findings align with those of larger studies that looked at first-time mothers over time, "suggesting that pregnancy-induced brain changes may be a ubiquitous phenomenon," Magdalena Martínez-García, a postdoctoral researcher in human neuroscience at UCSB, told Live Science in an email.

Elseline Hoekzema, a neuroscientist who studies the neurobiology of pregnancy at Amsterdam University Medical Center, agreed. "It's likely that these changes are at least partially representative for a larger population," Hoekzema, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

Nonetheless, Chrastil's brain map is only the beginning. Along with collaborators, the authors are launching the Maternal Brain Project, an international effort aimed at collecting similar brain scans from more pregnant people.

A few more have already completed their scans, and "they're all showing the exact same pattern of change at the time," Jacobs said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.