Parasitic worms cause terrible diseases — could the viruses they carry be to blame?

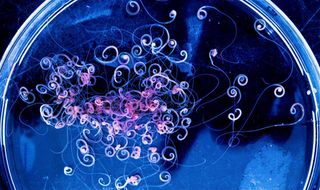

Roundworms harbor viruses, which could be responsible for these parasites' painful symptoms in humans, scientists theorize.

Roundworms, also known as nematodes, are a leading cause of parasitic infection worldwide, causing painful swelling, severe abdominal pain and even blindness. Now, scientists say that viruses carried by these worms may be one reason they cause such severe illness.

In a recent study, published in September in the journal Nature Microbiology, the researchers looked at more than 40 parasitic nematodes, zooming in on a molecule called RNA. A cousin of DNA, RNA helps cells make proteins and also forms the basis of various viruses.

The scientists uncovered 91 RNA viruses in 28 of the worm species studied, representing about 70% of the roundworm species that infect humans.

This study represents "the beginning of a whole other area of research on virology, pathology and more," Elodie Ghedin, a parasitologist and microbiologist at the National Institutes of Health who was not involved in the work, told Live Science.

Related: 32 scary parasitic diseases

Shannon Quek, study lead author and a parasitologist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) in the U.K., had been studying viruses in mosquitoes, and through that work, he came up with a way to find viruses within nematodes.

Quek built an algorithm to search for signs of viruses in mosquito RNA, Mark Taylor, the senior study author and a LSTM parasitologist, told Live Science in an email. "In an inspired 'lightbulb' moment, he decided to use the same algorithm to search parasitic nematode transcriptomes," meaning readouts of all the RNA in the worms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While mining publicly available roundworm data, the researchers looked for a marker that is seen in all RNA viruses: An RNA molecule that codes for a specific enzyme. By hunting for this marker, they identified genetic material from viruses hidden within the worms.

Only five of the more than 90 viruses the team found had been previously reported; most were newly discovered.

The team then wanted to see if there were signs of viruses multiplying in the worms. They looked at two worm species: Brugia malayi, which causes swelling of the limbs, and Onchocerca volvulus, which causes skin diseases and blindness.

In both worms, the researchers saw viruses under a microscope — specifically, they saw a virus called BMRV1 in the former and OVRV1 in the latter. In B. malayi, they saw the worm's immune defenses were raised against BMRV1. And when they mashed up B. malayi worms and studied what came out, they found viral proteins, suggesting those viruses were actively replicating.

Related: Parasitic worms infect 6 after bear meat served at family reunion

But do these viruses affect the humans that nematodes infect?

To investigate, the researchers isolated serum — blood but without clotting factors — from people who had been infected with either worm. They found antibodies against the worm-borne viruses, suggesting that people mount an immune response against them. These two viruses have only been described in the worms so far, making it unlikely that the humans could have been exposed another way.

The researchers now plan to explore whether the viruses drive any symptoms tied to these parasitic worms. O. volvulus, for example, has been implicated in onchocerciasis-associated epilepsy (OAE), a disease that leads to epileptic seizures. The worm's role in these neurological symptoms is unknown, but OVRV1 may be the culprit.

"The most likely candidate for driving disease is the rhabdovirus OVRV1," Taylor argued. Other rhabdoviruses include rabies, and broadly, they are known to infect and damage nerve cells. "This could be the elusive cause of OAE."

Some parasitic worms also harbor bacteria, like the microbe Wolbachia, which drives some of the diseases tied to roundworms.

"The system where you have a parasitic infection is not just an infection with a worm; it's that the host — the infected individual — has a worm that has bacteria, and the worm also has viruses," Ghedin said. "All of these are replicating; they're producing proteins which can make their way outside of the worm and interact with the host's immune system."

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Rohini Subrahmanyam is a scientist-turned science writer with a PhD in Biology and postdoctoral experience in Developmental Biology. She mostly likes writing about interesting creatures on our planet, ranging from zombie flies and regenerating worms, to intelligent octopuses and mysterious comb jellies.

- Nicoletta LaneseChannel Editor, Health