NASA shuts off Voyager 2 science instrument as power dwindles

NASA has turned off one of Voyager 2's science instruments as power conservation becomes crucial for the interstellar exploring spacecraft located 12.8 billion miles from home.

NASA engineers have turned off one of Voyager 2's science instruments due to dwindling power supplies on the spacecraft as it explores interstellar space.

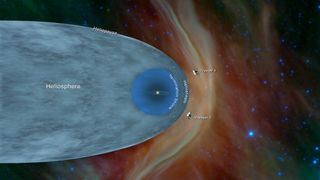

Voyager 2 launched into space on Aug. 20, 1977 and left the solar system on Nov. 5, 2018. It is currently 12.8 billion miles (20.5 billion kilometers) from Earth and is using four science instruments to study space beyond the heliosphere, the sun's bubble of influence around the solar system. NASA thinks that Voyager 2 has enough power to keep running one science instrument into the 2030s, but doing that requires selecting which of its other instruments need to be turned off.

Mission specialists have tried to delay the instrument shutdown until now because Voyager 2 and Voyager 1 are the only two active probes humanity has in interstellar space, making any data they gather unique. Thus far, six of the spacecraft's initial 10 instruments have been deactivated. Now, losing the seventh has become unavoidable, and the spacecraft's plasma science instrument drew the short straw. On Sept. 26, engineers gave the command to turn off the instrument.

Related: NASA's Voyager 1 probe swaps thrusters in tricky fix as it flies through interstellar space

The plasma science instrument consists of four "cups" collecting information on the amount of plasma, a fluid of charged particles, flowing past Voyager 2 and the direction of this flow. Three cups are angled toward the sun, monitoring charged particles in the solar wind while within the heliosphere. A fourth cup is angled away from the others to observe plasma in planetary magnetic fields and interstellar space.

This instrument was crucial in detecting the drop-off in charged particles from the sun, which indicated that Voyager 2 had crossed the boundary between the heliosphere and interstellar space in 2018.

"Mission engineers always carefully monitor changes being made to the 47-year-old spacecraft's operations to ensure they don't generate any unwanted secondary effects," officials at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which oversees the mission, wrote in a statement. "The team has confirmed that the switch-off command was executed without incident and the probe is operating normally."

The usefulness of the plasma science instrument was limited by the fact that the three cups angled toward the sun stopped collecting plasma after leaving the heliosphere and moving past the influence of solar wind.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Also, because of Voyager 2's orientation, the data it has harvested over the last few years has been further limited. The one active cup only provides useful data once every three months when the spacecraft makes a 360-degree turn on its axis. This influenced the decision to switch the plasma instrument off to conserve power rather than deactivating one of Voyager 2's other instruments.

Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are powered by decaying plutonium, and they lose around 4 watts of power every year. In the 1980s, several of their instruments were turned off after the two spacecraft finished investigating the solar system's giant planets. This granted both probes extra power, boosting their longevity.

A few years ago, the two crafts also turned off all non-essential instruments. Voyager 1's plasma instrument stopped working in 1980, and it was switched off in 2007 to preserve power.

Meanwhile, NASA engineers are closely watching the resources of Voyager 2 so they can decide when its next science instrument must be depowered to ensure the interstellar explorer can deliver science for as long as possible from this "final frontier" beyond the solar system.

Originally posted on Space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University