DNA and Genes

Genes are the blueprints of life. Genes control everything from hair color to blood sugar by telling cells which proteins to make, how much, when, and where. Genes exist in most cells. Inside a cell is a long strand of the chemical DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). A DNA sequence is a specific lineup of chemical base pairs along its strand. The part of DNA that determines what protein to produce and when, is called a gene.

First established in 1985 by Sir Alec Jeffreys, DNA testing has become an increasingly popular method of identification and research. The applications of DNA testing, or DNA fingerprinting within forensic science is often what most people think of when they hear the phrase. Popularized by television and cinema, using DNA to match blood, hair or saliva to criminals is one purpose of testing DNA. It is also frequently used for other benefits, like wildlife studies, paternity testing, body identification, and in studies pertaining to human dispersion.While most aspects of DNA are identical in samples from all human beings, concentrating on identifying patterns called microsatellites reveals qualities specific and unique to the individual. During the early stages of this science, a DNA test was performed using an analysis called restriction fragment length polymorphism. Because this process was extremely time consuming and required a great deal of DNA, new methods like polymerase chain reaction and amplified fragment length polymorphism have been employed.The benefits of DNA testing are ample. In 1987, Colin Pitchfork became the first criminal to be caught as a result of DNA testing. The information provided with DNA tests has also helped wrongfully incarcerated people like Gary Dotson and Dennis Halstead reclaim their freedom.

Latest about Genetics

50,000 'knots' scattered throughout our DNA control gene activity

By Emily Cooke published

The mapping of 50,000 mysterious "knots" in the human genome may someday lead to the development of new cancer drugs, researchers say.

CRISPR could soon be used to edit fetal DNA — are we ready?

By Julia Brown published

Medical anthropologist and bioethicist Julia Brown says scientists and nonscientists need to talk about whether and how we should use CRISPR to edit the fetal genome.

'Enhancing' future generations with CRISPR is a road to a 'new eugenics,' says ethicist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson

By Rosemarie Garland-Thomson published

"Eugenics seeks to improve by eliminating the characteristics considered at a particular time and place to be disadvantages and to maximize those considered normal."

'Who are we to say they shouldn't exist?': Dr. Neal Baer on the threat of CRISPR-driven eugenics

By Nicoletta Lanese published

Dr. Neal Baer discusses a new book about the incredible promise and potential pitfalls of CRISPR gene-editing technology.

Largest animal genome sequenced — and just 1 chromosome is the size of the entire human genome

By Tia Ghose published

Scientists sequenced the largest known animal genome in a species of lungfish — ancient fish that breathe air.

Some people recover from ALS — now, we might know why

By Emily Cooke published

A rare gene variant may explain why a subset of patients with ALS recover from the deadly disease.

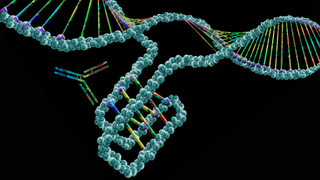

How does CRISPR work?

By Kamal Nahas last updated

CRISPR is a versatile tool for editing genomes and has recently been approved as a gene therapy treatment for certain blood disorders.

Why genetic testing can't always reveal the sex of a baby

By Maggie Ruderman, Kimberly Zayhowski published

Gender and sex are more complicated than X and Y chromosomes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.