Cholesterol-gobbling gut bacteria could protect against heart disease

Certain microbes in the gut microbiome may guard against heart disease by lowering people's cholesterol.

Bacteria present in some people's guts may help break down cholesterol, making them less susceptible to heart disease, a new study suggests.

The link between a high diversity of gut microbes and a lower chance of cardiovascular disease is well established. Previous research has shown that people with heart-related diseases, such as atherosclerosis, carry different kinds of microbes in their guts than people without the conditions. Researchers thought this may be related to a microbe-made enzyme called IsmA that breaks down cholesterol.

People whose gut bacteria made IsmA had less cholesterol in their blood than those whose gut bacteria didn't make this enzyme. However, the specific species of bacteria that make cholesterol-gobbling enzymes were not known.

Now, a study published April 2 in the journal Cell has shown that bacteria in the genus Oscillibacter break down cholesterol and that people who carry more of those bacteria have lower cholesterol levels than people with fewer of those microbes.

Related: 9 heart disease risk factors, according to experts

Uncovering the bacteria that metabolize cholesterol is "very interesting and exciting," Daoming Wang, a researcher at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, told Live Science in an email. Wang, a bioinformatician who studies the human gut microbiome, wasn't involved in the new study.

To understand how gut bacteria influence heart health, the researchers examined stool and blood samples collected from more than 1,400 people in the Framingham Heart Study, a decades-long study of heart disease risk factors.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team used different techniques to profile the microbial DNA in the stool samples. They also analyzed metabolites — the byproducts left over when chemicals like cholesterol break down. For each participant, the team then correlated these findings with known markers of heart health, like blood-borne cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

People with lower triglyceride and cholesterol levels had an abundance of Oscillibacter bacteria in their poop, the team found. They checked whether this correlation showed up in another, independent set of people and found that it did.

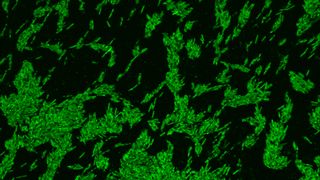

To confirm that Oscillibacter indeed metabolized cholesterol, the researchers grew the bacteria in the lab and exposed them to cholesterol marked with fluorescent tags. Using microscopy, the team looked for fluorescence within the bacterial cells, to see if the microbes sucked up the cholesterol — and they did.

The researchers then tracked the fate of the gobbled cholesterol and found that different bacterial species broke it down into various steroids. These steroids could be absorbed by other gut bacteria, resulting in decreased cholesterol levels overall.

To figure out which genes and proteins might help Oscillibacter break down cholesterol, the team used a machine-learning algorithm. The algorithm analyzes features of genes to predict how proteins encoded by these genes will look. This analysis revealed that genes that encoded proteins similar to IsmA were likely responsible for metabolizing cholesterol.

These results take us closer to understanding the "dark matter" of the microbiome, meaning the large number of gut microbial genes whose functions aren't yet known, Wang said. "This dark matter hinders us from seeing the whole picture of gut bacterial functionality."

In theory, tweaking the gut microbiome to boost cholesterol breakdown could be a strategy to reduce people's cholesterol levels, the study authors proposed. But before that can be done, we need follow-up investigations to better understand exactly how these bacteria break down cholesterol and how this can be used as a therapy, Wang said. We need detailed studies in lab animals, followed by clinical trials in humans, he said.

Nonetheless, Wang added, "it's very exciting to further explore the potential of manipulating Oscillibacter species as therapeutic interventions for managing cholesterol levels."

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Sneha Khedkar is a biologist-turned-freelance-science-journalist from India. She holds a master's degree in biochemistry and a bachelor's degree in microbiology and biochemistry. After her master's, she worked as a research fellow for four years, studying stem cell biology. Her articles have been published in Scientific American, Knowable Magazine, and Undark, as well as several Indian platforms such as The Hindu and The Wire Science, among others. Besides writing, she enjoys a good cup of tea, reading novels and practicing yoga.