Ancient Egyptians used a hydraulic lift to build their 1st pyramid, controversial study claims

A massive water-treatment facility located near the Nile River may have been used to build the pyramid of Djoser.

The ancient Egyptians may have used an elaborate hydraulic system to construct the world's first pyramid, a controversial new study claims.

Known as the Pyramid of Djoser, the six-tiered, four-sided step pyramid was built around 4,700 years ago on the Saqqara plateau, an archaeological site in northern Egypt, according to research posted to ResearchGate on July 24. The research has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Archaeologists have long wondered how ancient workers accomplished such an architectural feat — the structure contains 11.7 million cubic feet (330,400 cubic meters) of stone and clay — before the advent of large machinery like bulldozers and cranes.

Because the pyramid sits near a long-gone branch of the Nile River, researchers hypothesize that the ancient Egyptians utilized the water source to build the 204-foot-tall (62 m) pyramid by designing a "modern hydraulic system" comprising a dam, a water treatment plant and a hydraulic freight elevator, all of which were powered by the river, according to a translated statement from the CEA Paleotechnic Institute, a research center in France. They posit that the mysterious Gisr el-Mudir enclosure near the pyramid worked as a structure that captured sediment and water.

"This is a watershed discovery," lead author Xavier Landreau, CEO of Paleotechnic, told Live Science. "Our research could completely change the status quo [of how the pyramid was built]. Before this study, there was no real consensus about what the structures were used for, with one possible explanation being that it was used for funerary purposes. We know that this is already subject to debate."

Related: Mysterious L-shaped structure found near Egyptian pyramids of Giza baffles scientists

For the water-powered system to work, water would have flowed from the Nile to the dam, which would have stretched 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) long and had 49-foot-wide (15 m) walls lodged between the sides of two valleys to the west of the pyramid. The dam would have filtered out any sediment before the water traveled downstream to a treatment facility known as the "Deep Trench," which would have been 1,300 feet (400 m) long, 89 feet (27 m) deep and cut into existing rock. The facility would have contained several basins where sediment or particles would have settled at the bottom to prevent any clogs in the system.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

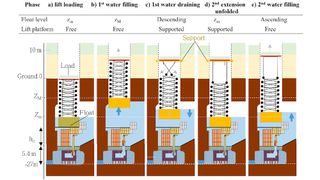

From there, a series of underground conduits would have tunneled water 92 feet (28 m) beneath the pyramid to a water-powered elevator. The force of water pooling into a central well would have been used to "float" stones up and down a shaft, delivering the heavy construction materials to workers as they built the "volcano"-shaped pyramid, according to the statement.

The elevator "would have played a crucial role allowing the water to fill inside the main shaft," Landreau said. "It's really a gigantic facility and shows that water was the fuel used to build the pyramid. The elevator would have had filling and emptying cycles that allowed the stones to go up to the construction level in a volcano-like fashion."

Landreau said this wouldn't be the first time the ancient Egyptians used water to move supplies; they often used the Nile to transport building materials down the river.

However, not everyone is convinced that the Egyptians used a hydraulic system to build the pyramid.

"My biggest concerns about the study are that no Egyptologists or archaeologists were directly involved and that the authors actually question the use of the Djoser Pyramid as a burial site," Julia Budka, an archaeologist at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, told Live Science in an email. "Scientifically, their hypothesis is not proven at all, and they themselves say at the end of the article that it would be necessary to conduct geological studies and sample analyses both inside and outside the areas in question to get a more accurate understanding of the proposed hydraulic system — not only of its operating time, but in general."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff wrtier and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Most Popular